The vertebrae of two centuries? [1]

Red light! Statues! We all froze, and now must make sure that this freezing-in-place is not broken, that the cessation of motion is an ongoing present. The slightest infraction of the non-motion in fact disrupts our progress. Because motion frozen in time is doomed to eternal failure, as non-motion means death, and stopping time or its inexorable, undefeatable motion is one of the foundations of existence. It was Heraclitus, the presocratic Greek philosopher, who saw in motion a dynamic expression of contrast, declaring that “You cannot step into the same river twice”.[2] The river is in a constant motion of change, and once you’ve stepped in it, the moment of entering cannot be reenacted, the same situation cannot be entered, since time has passed and the river has passed (water under the bridge): the river is different and the reentering is nothing like the first entering. This paradox of overlap between motion and the lack thereof is what this exhibition is about, and what life is now about.

The exhibition features installations that make up conversations on this subject from different, complementary viewpoints. Some installations are site-specific, explicitly displaying the dialectics of action and inaction; others are kinetic works that suggest anti-machines, in that their motion is repetitive and continuous and yet Sisyphean, as it leads nowhere and renders its underlying progress (production) unnecessary; some indicate the absence of kinetics through images and signs of stuckness, where inaction is alluded to by way of opposites. A show of defamiliarization between motion and stoppage, where every double negation of motion calls up a positive sense of it. A formal syntax wedded to a formal resemblance of an exhibition that strives to call up, in the words of Hal Foster, the “spirit of irreconcilability”, a gust of internal contradiction.[3] One cannot step into the same river twice, and the more acutely so here and now, during war. No other choice but to give in to stasis – of body, of action, of consciousness – while in motion, and to continue moving. The idea of identifying this double develops in the course of curation, wishing to create presence through a syntax of installations and interventions in the architectural space. An event of suspended duration that allows the conceptual framework to work itself out through specific examples, to use Joshua Simon’s definition of a contemporary art exhibition. For Simon, such an event relies on metastability, a term borrowed from physics to describe “a state characterized by small points of contact interfacing and connecting with great force and resembling a pile of sand about to collapse. Each grain of sand touches another grain at the smallest point and with the greatest force. Thus, the pile, as a multi-bodied puzzle poised to collapse, constitutes a stability event of suspended duration.”[4]

The suspension of stability is itself rooted in paradox. The value of stability as a temporary value is also present in the historic setting of the Stern house, today the Edmond de Rothschild Center, which hosts this exhibition. The house was built in 1928 by Jewish architect Judah Stempler, and further built in 1933 by architect Arieh Sharon, for the marriage of the Stern and Krinkin families of “Little Tel Aviv”. During the preservation efforts in the 2000s, original architectural elements of the foundational house were reconstructed and restored, including apertures, windows, and shutters (preservation architects: Ilan Kedar and Haviva Even).[5] The works in the exhibition settled with dubious ease into the ground floor, and while they occupy the present tense, they include the past’s perspective by addressing the house’s built heritage. Various architectural elements served to inspire and drive setting-appropriate actions, with the intent of creating a spatial experience that is not divorced from temporal layers.

Inside the house, hanging by a thread, is a model of an East-European-style house by Ira Prohorova, as the proportions of the contained space are different than those of the space containing it. The transparent house with its open windows invites one to look within, but in fact its exposed outlines indicate that the gaze has been reversed and is now directed from the inside out. A house looking at a house, each searching for itself in the other. Questions of immigration and identity bear a spatial and temporary presence, and draw a connection between a living space with its former occupants and an exhibition space with its present-day spectators.

We are met with a veiled gaze from dusty aluminum shutters by Nitsan Ben Zimra. It seems as if their eyes are closed. In leaning on the wall, they hint at a future potential for functional motion, yet this potential remains unfulfilled, as the blinds are tied with cotton string to stop the gaze. The string’s softness becomes a formal show of force that prevents the possibility of motion, the readymade is “dolled up” with a rhythm that varies between crafts and abstraction. A door’s teleology, Georg Simmel would say, points from the outside in, yet the threshold is bidirectional, allowing a simultaneous motion from the inside out.[6] Like a door, the window is an element of both separation and connection, but its teleological direction is from the inside out. The window is open for gazing outward, yet looking from the outside allows for peeking. Returning our gaze from the room’s floor below is a pile of white sand made of salt grains and baking soda, while it collapses inward and makes this collapse an event of sustained stability.

In another room, a dining table by Roni Hagai is rocking. Set amongst splendor, without chairs around it. The only thing going round and round is a rope that connects the center of the table to a motor. The rattle of constant motion cannot awaken from its slumber the pond of sugar water set into the table, making it seem like even the tiniest tectonic motion is frozen. The honey trap is no match for it. According to Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra, ”all the creatures have movement: even the heavenly bodies, namely the lights and the stars have movement as that of the human soul.”[7] The table’s soul is audible in the motorized pulse, which contains the motion of the stilled world. Even the house’s occupants have fallen still, and yet it moves.

In the apse of the house’s portico, the wind regimen directs the sound of bells. Their jingling mingles with the motor’s mechanical noise and the din of the Nonstop City. In an inside room, the bells are heard once more, but this time against the din of another city, where the sound of the mosque’s muezzin mingles with that of a church. The sound reveals an image of bell-shaped earrings in the ears of Noga Shalit Glick, their movement simulating a forward gait generated by the negative shake of her head. This is a double negation that leads to a sense of positivity. In a shoulder stand that requires stability, with a water bowl balanced on the soles of her feet, the artist negates any possibility of collapse, even though she hints at one in a dialog about a terrifying dream between a living daughter and a dead father. Not even a pulse is heard, yet it is seen in the nearby image of a metronome, in the photographic self-portrait of Danielle Liberman. The artist, dressed in black with her polished toenails exposed, is squatting low, her gaze either lingering or freezing on the silenced object. “Like a beast once limber you [she] look back, […] to contemplate your[her] own tracks,”[8], wishing to propel the unpropelled, to create the possibility of hearing a continued pulse in the confusion of existential sounds, to continue seeing action in its absence.

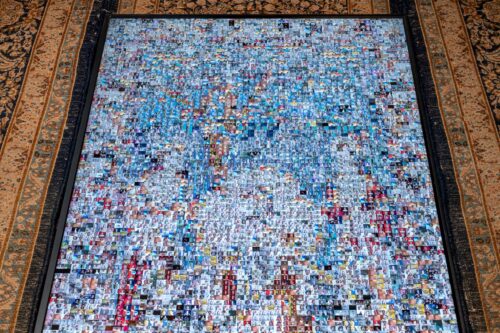

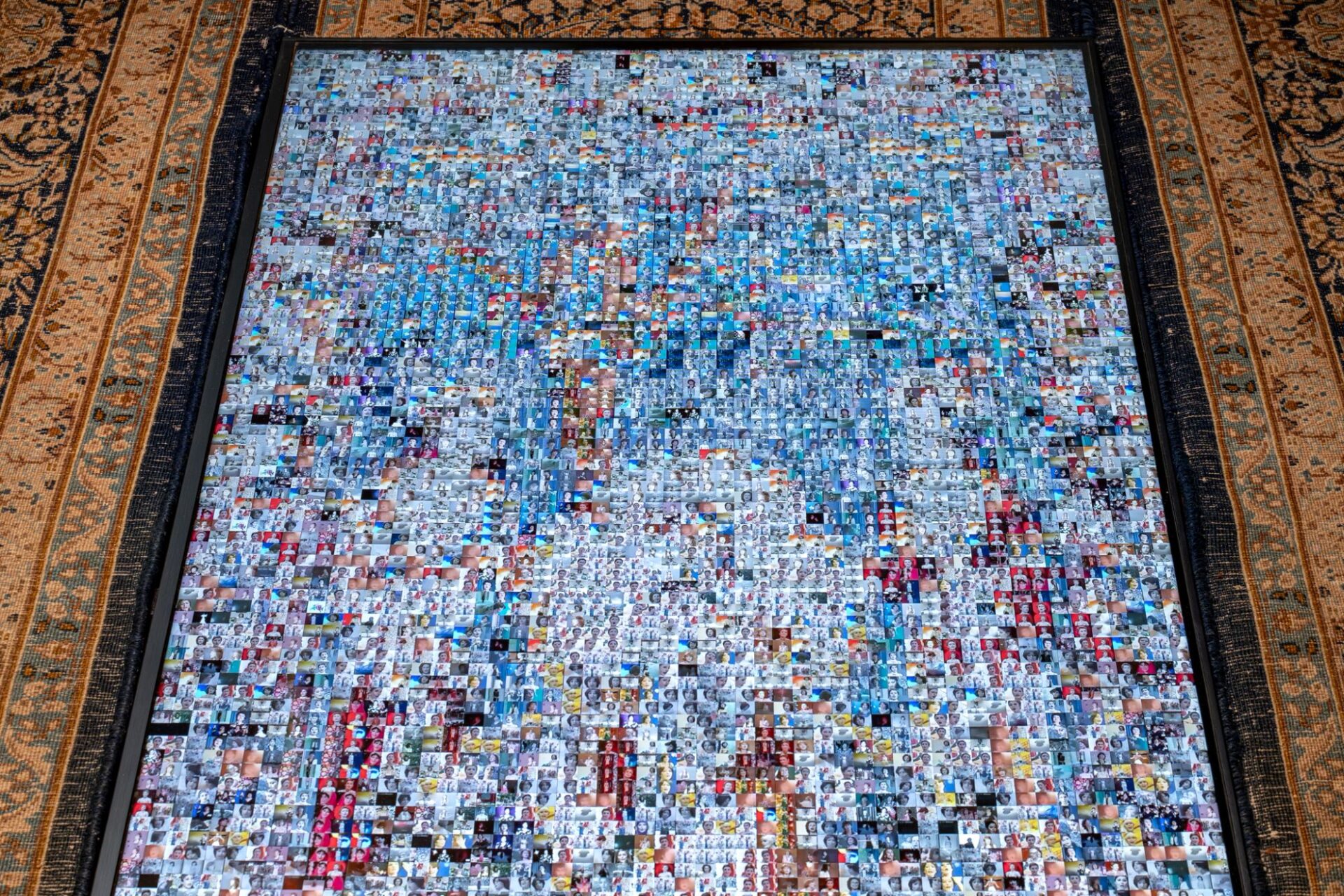

The house’s architectural plan is characterized by symmetry of front and rear. Concave shapes mirror each other, twice recalling a cathedral’s apse, and with them David Mottahedèh communicates. The installation deals with the act of reconstruction, looped repetition of what was stopped in one dimension (past) and continues to move in another (present), in a motion of waiting. The key motifs are related to elements taken from Iranian culture during the Islamic revolution crisis in the end of the 1970s – carpet weaving and women’s singing. One is perceived through sight and the other through hearing, yet these are disrupted. Famous Iranian singers such as Simin Ghanem were silenced and stopped singing, but continue to sing on YouTube. The double meaning of stopping and motion, of cutting off and connecting, is manifested on one hand in inanimate objects (a carpet) that bear an absent historical weight; and on the other hand in their new kinetic format (a screen), based on a code that converted them from one formal system to another. The layers piled up in the books, carpets, and screens combine into a sign language that comprises a series of utterances dismantled into units of expression and of time. They challenge the whole, while at the same time constituting it. Some say things must stop in order to sustain life. Must they?

The outline of the house/exhibition floor is surrounded by a baseboard – vertically installed tiles that frame the floor tiles. The baseboard tiles serve as the reference point for the concrete-in-earth castings Cheli Jusewitz poured by digging holes in her own backyard. The length of the casting in her private space corresponds to the length of a wall in the public display space, wondering at their intermingling. The outline is not continuous, since during its extraction from the ground it was broken and segmented, and its meaning lies not in continuity but in intermittency, in the gaps. With their low closeness to the ground, both materially and formally, they seem like infrastructural remnants that floated to the surface or as exhumed bones. Their weight as the complete thing is the same as the weight of the gaps between its parts; our eye imagines what is, and is left with what isn’t. In “What is the Contemporary?”, Giorgio Agamben discusses the duty of the poet, “who must firmly lock his gaze onto the eyes of his century/beast, who must weld with his own blood the shattered backbone of time”.[9] The poet, as the image of contemporariness, is the breaking and rewelding of the century’s vertebrae, preventing time from constituting itself while at the same time tasked with healing the fracture. It seems that not only is time shattered; but the organs of the house, which are also the organs of the body, are shattered as well.

The dispute over time is as contemporary as it is ancient. Aristotle, the classical philosopher who argued the uniqueness of the unmoved mover, was given a medieval interpretation by Thomas Aquinas, who said that motion is simultaneously action and its potential, meaning that it is as concrete as it is a possibility.[10] To me, investigating the simultaneity of motion and its absence was an existential necessity. Relying on the double negation that leads to positivity is an optimistic moment asking to be beheld.

[1] “My century, my beast, who will manage / to look inside your eyes / and weld together with his own blood / the vertebrae of two centuries?” From Osip Mandelstam’s poem “The Century ”. In: Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, Stanford University Press, 2009.

[2] Heraclitus: “You cannot step into the same river twice” (fragments B and ancient testimonia A) in: H. Diels and W. Kranz, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, 6th edition (Berlin: Weidmann, 1951-52). In: James Lesher, Heraclitus’ Poetic Ideas, https://philosophy.unc.edu/people/james-lesher/heraclitus-poetic-ideas/

[3] See: Hal Foster, What Comes After Farce?: Art and Criticism at a Time of Debacle, New York: Verso, 2020.

[4] Joshua Simon, “Writing with a pen she does not hold – Thoughts about curating” (“Ktiva be’et she’eino be’yada – Makhshavot al otzrut”), Bezalel Journal of Visual and Material Culture, 10, 2024. [Hebrew].

https://journal.bezalel.ac.il/he/article/4554

[5] From the preservation file for Stern House, Rothschild 104 St., Tel Aviv-Yaffo. Recorder: Amir Genislaw, architectural firm: Ilan Kedar and Haviva Even, 2013, p2.

[6] See: Georg Simmel, “Bridge and Door”, Theory, Culture & Society, 11:1, (1994): 5-10,

https://doi.org/10.1177/026327694011001002

[7] Abraham ibn Ezra’s commentary on Isaiah 57:15: “For thus says the One who is high and lifted up, who inhabits eternity, whose name is Holy: “I dwell in a high and holy place, and with the oppressed and humble in spirit, to restore the spirit of the lowly and revive the heart of the contrite.” In: H. Norman Strickman, Abraham ibn Ezra: on seeing God’s back, Hakirah -The Flatbush Journal of Jewish Law and Thought, 23, 2017, p. 122.

[8] Mandelstam’s poem “The Century”. In: Agamben, “What Is the Contemporary?,” p. 43.

[9] In: Agamben, “What Is the Contemporary?,” p. 42.

[10] Thomas Aquinas, “Argument from Motion”, accessed December 4, 2024 https://dma.hamline.edu/~asnyder06/god/arguments/theist/aquinas-five-ways/argument-from-motion.html