Preface

In the last month, we have woken up to a different, new and unsettling reality. A reality that compels us to rethink our lives.

In this emotional whirlwind, alongside existential reflection, also the quotidian demands renewed thinking, and sometimes both thoughts merge. We found ourselves looking at the exhibition Eye Socket, which we curated. It became apparent to us that the image of the eye socket – an image that clarifies the need for a house that can contain the internal, the identity of the self, and that enables direct looking – suited the present situation.

The house guards from real things outside while it also protects the soul from sights the eye sees. In the 19th century, it was widely believed that the last image a person sees before death is imprinted on the retina. At a moment such as the present one, we want to offer or to at least imagine other sights than the ones seen this month, ones in which a sliver of comfort can be found.

Yaelle Ben-Ami and Orit Bulgaru

Sight peeled the real from the hidden without fully exposing the truth. Once seen, it can never be unseen. All I have wanted since is to look inward in order to be inside what protects me.[1]

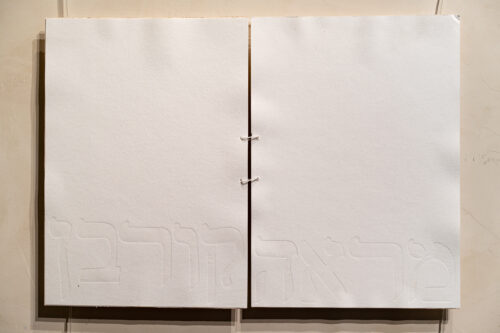

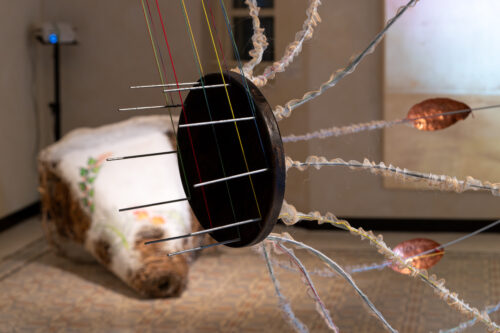

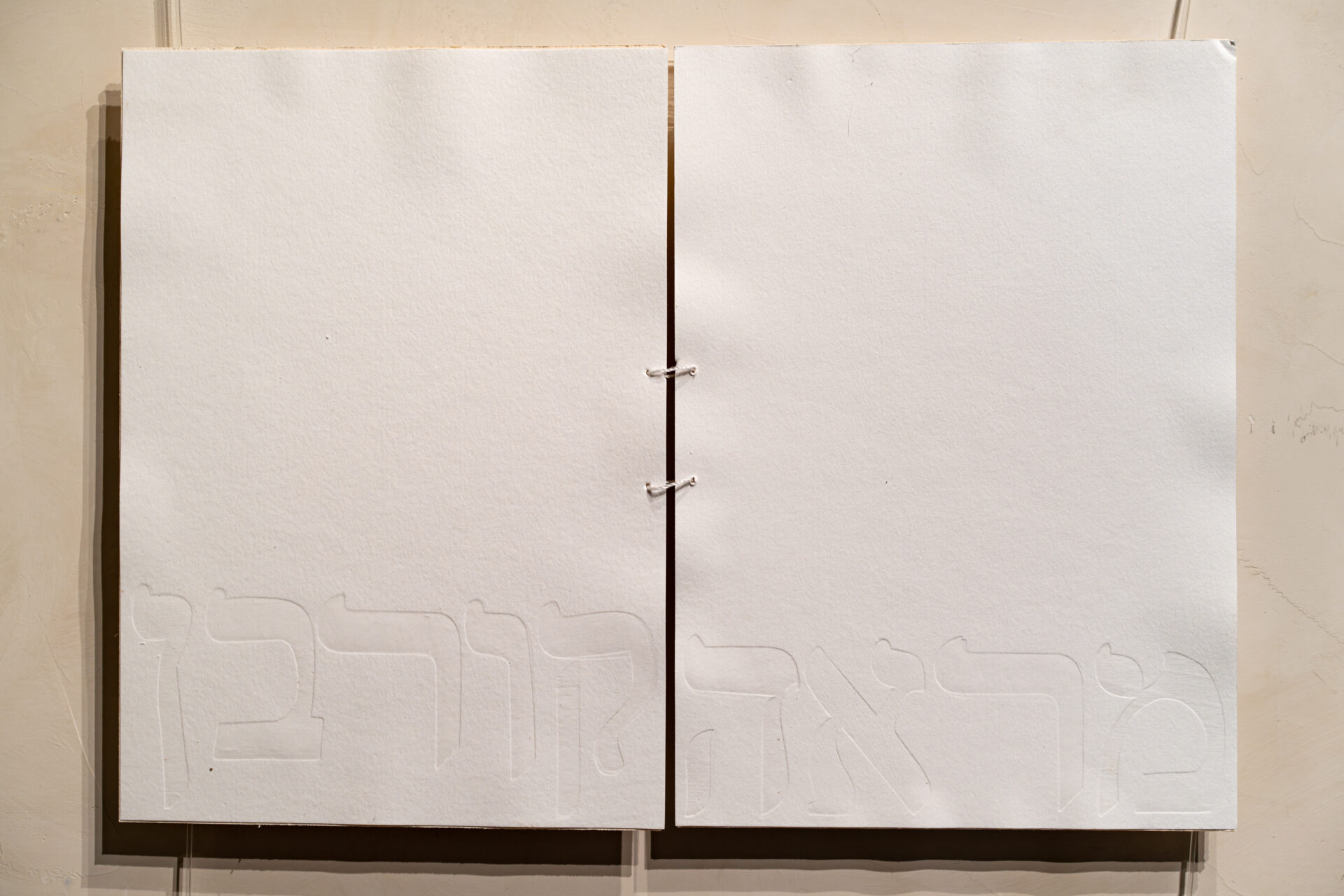

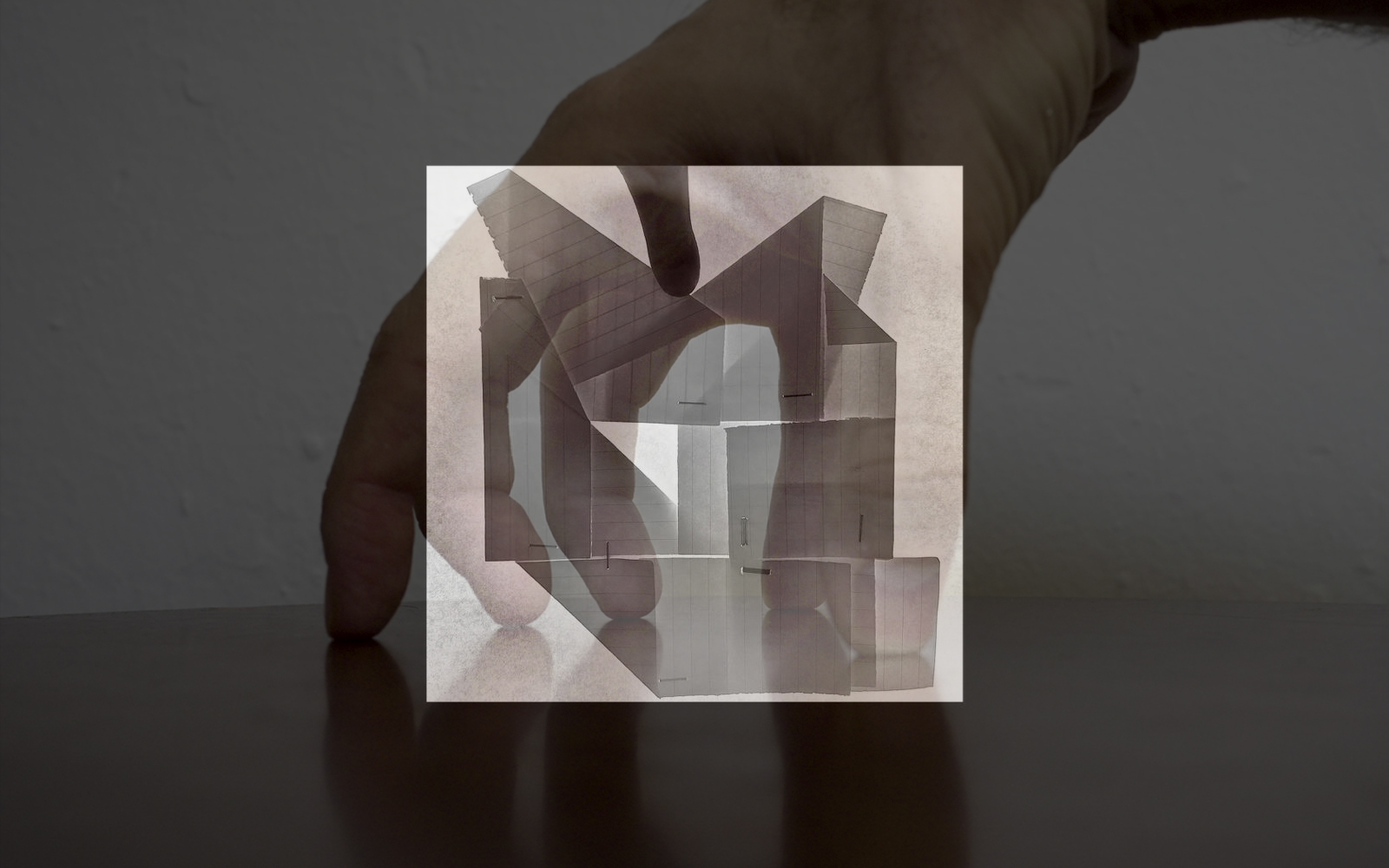

The exhibition Eye Socket presents video and installation works created by nine members of the Edmond de Rothschild Center network who have completed their studies in various departments in schools of art and design in the last five years. The eye socket is the point of departure for the new projects in diverse media made especially for this exhibition. The participants responded to this image and its various biological-neurological and psychological meanings and to its concrete and phenomenological connections to vision and knowledge.

The eye is situated in a cavity in the skull that is called the eye socket. The socket holds the eye as well as the muscles responsible for its movement and the nerves that connect it to the brain. It functions as a protective container supporting vision and as a shock absorber. The eye socket forms a transitional zone, both in literal and figurative terms, connecting the internal realm of the body to the external world. It functions as a corridor, bridging the subjective internal experience with the external field of vision.

In his essay “Eye and Mind,” Merleau-Ponty discusses the relationship between the external and internal and the body that connects them as the intertwining of vision and movement. The body senses the visible object, which provokes and stimulates a reverberation of the thing inside the body:

Shall we say, then, that there is an inner gaze, that there is a third eye which sees the

paintings and even the mental images, as we used to speak of a third ear which grasps

messages from the outside through the noises they caused inside us?[2]

And what does the inward-looking third eye see? The eye socket foresees knowledge, and thus, in one sense, it evokes the stretch of time in anticipation of the unknown, and in another sense, it is also a potential space for a moment of revelation. As an image, it symbolizes transition: between darkness and light, the visible and the hidden, the private and the public, life and death, knowledge and lack of knowledge – transitions of changing rhythms that echo knowledge and the lack thereof and the movement in between.

The focus on the eye socket turns the spotlight on the inner space. However, this is not only a formal aspect; it is an inner space that is by nature caught between things – between what is already known and what is yet to happen – an inner space that contains historical consciousness, and within it also a moral order, and perhaps even the promise of what is yet to come. Merleau-Ponty writes:

The enigma derives from the fact that my body simultaneously sees and is seen. That

which looks at all things can also look at itself and recognize, in what it sees, the “other

side” of its power of looking. […] a self, then, that is caught up in things, having a front and a back, a past and a future.[3]

[1] Israel Eliraz, “Entryway,” in What Happened After? How Much Time Is After? Slowly, Details of a Moment that is Eternal Are Becoming Clear, Tel Aviv: Afik, 2015, 14 [Hebrew]. Translation, OB.

[2] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind,” from Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception, ed. James M. Edie, trans. Carleton Dallery, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1964. Revised by Michael Smith in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader, Galen A. Johnson, ed., Evanston: Northwestern Univ. Press, 1993, 4.

[3] Ibid., 3.