In an apocalyptic and militant reality, where governments and ideologies are crumbling, God is absent, and artificial intelligence is accepted as absolute truth, many of us are seeking a way towards peace and security in the midst of the maddening din. In the exhibition Mindfulness at Rothschild, ten artists offer reflections on transcendence[1] in the current “post-New Age” (that began in the second half of the 20th century) reality. A place where matter meets spirit in the hopes of finding an alternative to the material rationality that will be a balm for the soul. The artists relate to both local and universal aspects in the context of religions, science fiction, reincarnation, nature worship, and other body-mind practices.

There is a misconception that this current mood of extremism is fueling the metaphysical expression in art, although existential questions and thoughts about spirituality and meaning were present also in early Israeli art in various conceptual and material iterations. For example, Reuven Rubin’s 1923 work The God Seekers, or Mordechai Ardon’s works dealing with metaphysical aspects of the artist. According to art historian Gideon Ofrat, “For Ardon, notwithstanding his enormous sensitivity to the horrors of the Holocaust, and his amplification of images of the catastrophe to cosmic theological dimensions, it is doubtful whether, with his creative intuition, he penetrated the darkness of time past and future, to mark some visionary map.”[2]

It is worth noting that in the discourse of modern art in the 20th century, little space was devoted to discussion of spirituality or mysticism, and the adjective “New Age” was even considered pejorative (although in some instances one could say that the spiritual is not far removed from the abstract). And yet, from the second half of the 20th century until today, preoccupation with aspects of the metaphysical and spiritual in art has been growing steadily. No longer perceived as “negligible,” this interest has instead achieved recognition and status in the discourse, a trend visible also in Israeli art. Some examples are Michal Na’aman’s “Lord of Colors, 1976” series, which, along with the choice of materials (masking tape), which the artist used to treat the idea of visible and invisible, deals with questions about the Divine; Moshe Gershuni’s God, Full of Mercy, from the 1980s, which express a different plea to God; Dorit Feldman’s multidimensional works from the 1990s, in which Kabbalistic symbols hold a key place as a mystical code for the reconciliation of space and time; and in the 2000s, the work of artist Shay Azoulay, about whom Ellen Ginton wrote: “Azoulay himself paves the way to linking his painting to mystical and Torah-minded worlds.”[3]

In the exhibition, the emerging discourse among the group of artists expresses our musings in dark times, when a torn and bleeding Israeli society is undergoing social, political and economic fracture and chaos, without a shepherd to guide it. In the context of present events, art expresses a spiritual search for a path, for the light.

In Ohad Lowy’s monumental installation, two separate surfaces connect to form an entrance of sorts to the exhibition space. On the upper surface, the viewer looks up at an abstract geometric flow chart composed of red cotton threads that form a line or path between points. On the connecting surface, a patina relief of palms invites the viewer to read and decipher (the pseudoscientific practice of chirology or palm reading, which claims to predict a person’s future through reading their palms, has ancient roots in various cultures and religions). For Lowy, the idea of mapping is an act of controlling and ordering a space. A grid establishes control through the creation of an image atop a surface. It is the meeting of the material with the spiritual plane. Through it, Lowy connects with and is influenced by the ideas of the abstract artists. As theorist Rosalind Krauss remarks, “We will find that Mondrian and Malevich are not discussing canvas or pigment or graphite or any other matter. They are talking about Being or Spirit. From their point of view, the grid is a staircase to the Universal.”[4] In his work, Levi seeks to mediate the spiritual and the sublime for the viewer. His is not a religious sublime, but a secular one, related more to the human spirit than to a divine being. He believes that a spiritual state of consciousness can exist when coming to gaze at the work if we first rid ourselves of cynicism and skepticism.

In a video work involving digital manipulation, the image of artist Uri Zamir floats in a cloud-filled space to meditative sounds. Guided imagery meditation, in which the meditator imagines himself floating in a heavenly reality, is made evident. The primordial fantasy of levitation becomes a possible reality. Zamir engages in a variety of techniques, materials and media fields. He is interested in how everyday actions can be processed into fantasy. Seeking to intensify the drama and conflict by applying the fictional to the real, he aims to create a mythical dimension that charges space with a new narrative.

Yaala Getzov Kleiner expresses her escapism in the fantastic territory she conjures through the technique of collage. She obsessively and densely populates this zone with contrasting snippets of nature from various sources such as photographs from magazines, the Internet or paintings, which are combined eclectically on four adjoining windows to form a single unit. The result is a seductive “Horror vacui” of elements crammed together that leave no room for breathing or for the sustaining of life, and conceptually refers to the oversaturation of information culture, the hoarding, preserving and consuming of life in the present age.

For Yishai Hogesta, the everyday becomes a sublime entity. His works are characterized by textures, compositions, and color surfaces over which he applies compressed stains, lines and forms; shapes in the making, random marks that can be read either as a narrative drawn from science fiction or a topographic map. Hogesta combines the urban with another odyssey. He plucks objects and elements from the familiar space and embeds them in a new and obscure context that creates a parallel reality, suggesting an alien world. His creative materials (industrial paints, sprays, pencils) serve as the physical mechanism through which a new reality fixed in the material can be formed.

Lior Katz’s installation contains two symbolic-spiritually charged materials—beach sand and the circle shape—which express a thing “in the making,” that is, something continually coming into being. On a base of plexiglass Katz draws a circle using beach sand (an act reminiscent of a childhood game), where the slightest breeze or random step can alter its shape. A singular moment, like the circadian rhythm in nature. According to Katz, if the circle strays from its shape, it seeks to “correct” itself, just as faith requires immediate upkeep. In spiritual teachings, the circle symbolizes the life force and protection against chaos and strengthens belief in the universe.

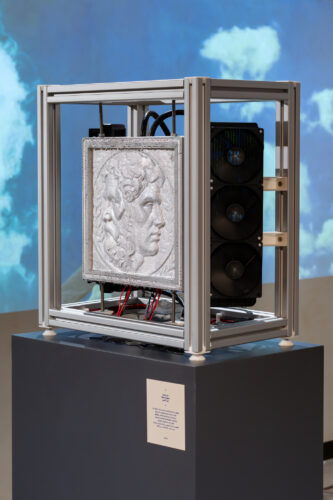

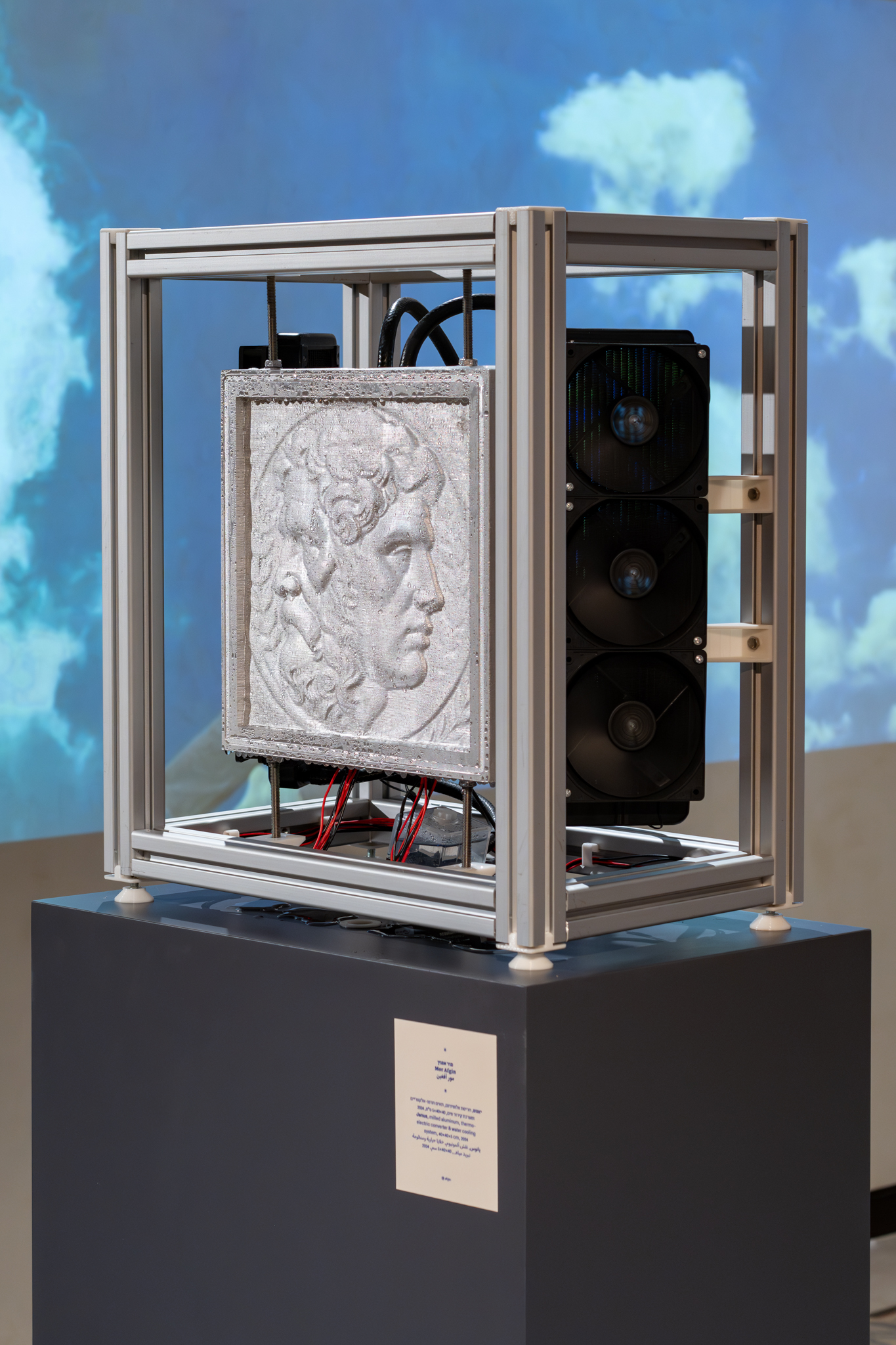

Mor Afgin creates circular movement in cosmic time and space consciousness; the circulation of fluid mechanics[5] and contemporary technologies serve him as both expressive idea and visual form. Working in the technique of metal milling, Afgin borrows the mythological image of the two-faced god Janus (an image that corresponds with his previous work, Two-headed Donkey) to simulate a strategy for the creation of coded, relative information. Janus is considered as presiding over beginnings and endings, in this case: cooling–freezing–thawing–sweating, ad infinitum. The relief with the doubled headed image is the mechanism that generates continuous movement, which operates in a process of quasi-diffusion: on the one hand, it harvests the surrounding moisture, which depends on temperature and compression, and on the other, it spreads heat to the surroundings. It is a game of reactive energetic modes of accumulation between two masters, between systems of accumulation and control, between abstract and solid, between existential and mythical dimensions; evolving creation as a repeating DNA helix unit. Afgin squares the circle[6] in perpetuity, aiming to express the impossible through rational tools.

In Neta Moses’s film How to Be Alone, a young woman wanders the virtual and real world in an existential quest for the right way to live. The film examines the paradox of the Internet: an endless stream of consciousness and knowledge, with no absolute truth. The film was shot in 2018/19, in Brighton, when Moses was an exchange student there, a time when she became consumed by existential questions. Moses assumes the roles of actress, director and editor (her twin brother, the musician Guy Moses, is responsible for the sound. A significant part of her question of existential loneliness involves the twins’ synchronicity). In the film, she wanders in nature equipped with a computer. A shifting axis between nature and technology references the gap between narrative cinema and the work of editing and of embedding virtual content. The work was first screened in 2020, during Corona, when the loneliness and isolation imposed by the epidemic added yet another relevance. The film is shown here for the first time in its continuous version and includes another episode with scenes from 2023 to the present day. The question of the meaning of existence and of maneuvering within it gives validity to the here and now.

The documented performance The Breathing Tree by multidisciplinary artist Einav Shvartz expresses our desire to disconnect from the tumult, to escape the pollution, noise and non-stop tasks of daily life, and to breathe in nature, inhale a bubble of clean oxygen, and unwind. Shvartz allows us to realize this aim through the device of the “breathing tree”: all we have to do is enter the trunk of the tree and breathe. Like her previous works, this performance corresponds with her autobiography as the daughter of a magician—in adulthood she too seeks to create magic, to bring a breath of nature into the hustle bustle of city life.

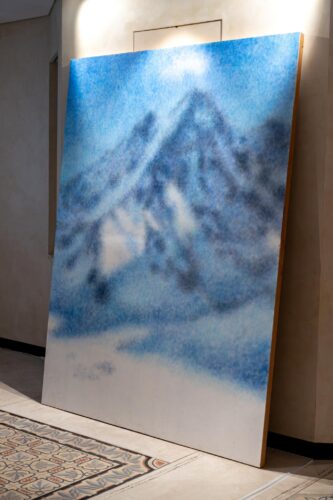

Ron Chen deals with places where the mystical qualities of an image allow for the fusion of body and mind. According to the artist, the saying of Rabbi Nachman of Braslav, “You are where your thoughts are, make certain your thoughts are where you wish to be,” refers to the experience of the disconnection of mind from body and hints at the possibility of navigating movement, like a wanderer in search of a path to his destination. His work Snowed Mountain expresses that amorphous place deemed “Sublime,”[7] where man stands before the infinity of nature. Man’s smallness in the face of sublime nature characterizes the northern Romantic traditions as formulated in 18th-century thought and articulated by artists such as Caspar David Friedrich in his work Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818, which expresses the modern human experience of incomprehensibility of the universe.

A safe haven in a dystopian reality is at the center of Shani Avivi’s installation and video work A Place to Be. At a time when the home has become an unsafe place, shelter takes on an existential, relevant, everyday meaning. Avivi’s installation includes objects necessary for a prolonged stay. The television is both useful object and treated ready-made for screening the video work. In the video, a tank serves Avivi as a living quarters; an armored vehicle designed to defend a territory becomes a territory itself. The female character inhabiting a tool of demolition tries to turn it into a feminine space fostering life and growth. Not satisfied with only the tank’s interior space, she goes out into the surrounding forest in an attempt to correct a past human injustice. The trunks of the trees in the forest on the Germany–Poland border are crooked. Researchers speculate that the distortion was a result of the enormous heat emitted by the tanks during World War II. The character engages in the work of wrapping (heating) trees in an era of climate crisis and global warming in the wake of the human conquest and disruption of nature. The fundamentally absurd situation also casts doubt on the eco-feminist attempt at repair. The multidisciplinary work, spanning sheltering spaces that change in place and time, also offers an absurd spiritual dimension, exaggerating the perspective that distances us further from happiness—war, borders and the exploitation of nature.

Nurit Tal-Tenne, curator

[1] Transcendence is a state of being that has overcome the limitations of physical existence and according to some definitions become independent of it. In most religions and traditions, this belief is rooted in the concept of the sublime which contrasts with the notion of a god or (the Absolute) that exists exclusively in the physical order (immanentism), or indistinguishable from it (pantheism). Transcendence can be attributed to the divine not only its being, but also in its knowledge of it. Thus God may transcend both the (physical) universe and knowledge (that is beyond the grasp of the human mind). Wikipedia.

[2] Gideon Ofrat, “The Metaphysical Intuition of Israeli Art,” The Storeroom of Gideon Ofrat, July 2014. [Hebrew]

[3] Ellen Ginton, “The Illuminated Painting,” Superpartners: Shay Azoulay, Reuven Israel, exh. cat., Tel Aviv Museum of Art, July 2011, p. 108.

[4] Rosalind E. Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, MIT Press, 1986, p. 10.

[5] “Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the mechanics of fluids (liquids, gases and plasmas) and the forces on them” (Wikipedia).

[6] “Squaring the circle” is sometimes used as a metaphor for an attempt at an impossible task.

[7] Edmund Burke linked the beautiful and sublime, claiming that the essence of beauty is pleasure and that of the sublime is pain and anxiety. He connected beauty and the sublime through the concept of delight, in other words, pleasure driven by anxiety. Hence the sublime is pleasure aroused by anxiety, a state of astonishment in which all motions are suspended. Burke sought to distinguish this anxiety by defining it as removed from any real possible danger, that is, the physical proximity of the individual is safe even though his gaze and givenness are motivated by a feeling of anxiety arising from a feeling of insecurity.