Another world is flowing and churning beneath our feet. A world where life and death mingle, a percolating melting pot where all signs of social status become blurred. For the last 150 years, it has been shaping Western society, reflecting its politics and, ostensibly, keeping it functioning, orderly and clean. The sewer contains within it a disturbing replica of the city that dwells above it, tracing its movement as it spreads like a kind of giant intestine that clears away the contents of our bowels. The exhibition Spring Water seeks to highlight the impending danger of this underground digestive system overflowing and bathing us all in filth and slime, regardless of religion, economic status or worldview. As early as 1867, Karl Marx foresaw just such a metabolic rift due to excessive exploitation of organic resources that will lead to the disruption in the relationship between human and nature. According to Marx, damage to this essential process will inevitably lead to deterioration in the condition of human life to the point where its very viability is threatened – in other words, a climate crisis. The natural disasters now plaguing us, in the form of hurricanes, flooding, earthquakes and sinkholes, will increase and could, among other catastrophes, cause an explosion of the sewage system that sends all the muck and mire back into the ground, resulting in a catastrophic disruption to the “proper order.” Our modern hygiene culture, which closely links the “clean” and the “appropriate,” and which dictates so many aspects of our daily life, will be forced to change beyond all recognition.

Today, a functioning or non-functioning sewer in any residential area is indicative of local public policy and a sign of geo-economic disparities. The first in the Western world to boast a sewer system that sent waste into cesspools underground was the modern city of London. For years, the city’s residents had been content for their feces and garbage to flow into the Thames River. That is, until a severe drought in 1858 dried up the river and led to what became known as “The Great Stink.” Members of parliament who rode around the city in sealed carriages were able to ignore the phenomenon for a while. But when the stench reached Westminster and politicians began dropping like flies, the decision was taken to build an orderly infrastructure that would bury the strong smells – out of sight, out of mind. At first, this new invisible river led the city’s inhabitants, accustomed to living next to excrement, to wonder what life forms were taking shape in that dark abyss. Horror stories were invented about octopuses, rats, turtles and women, along with a host of urban legends about mutant and hybrid creatures. The most famous among them is the one about the alligators who not only prowled the sewers of New York but also, from time to time, ventured above ground to prey on human flesh.

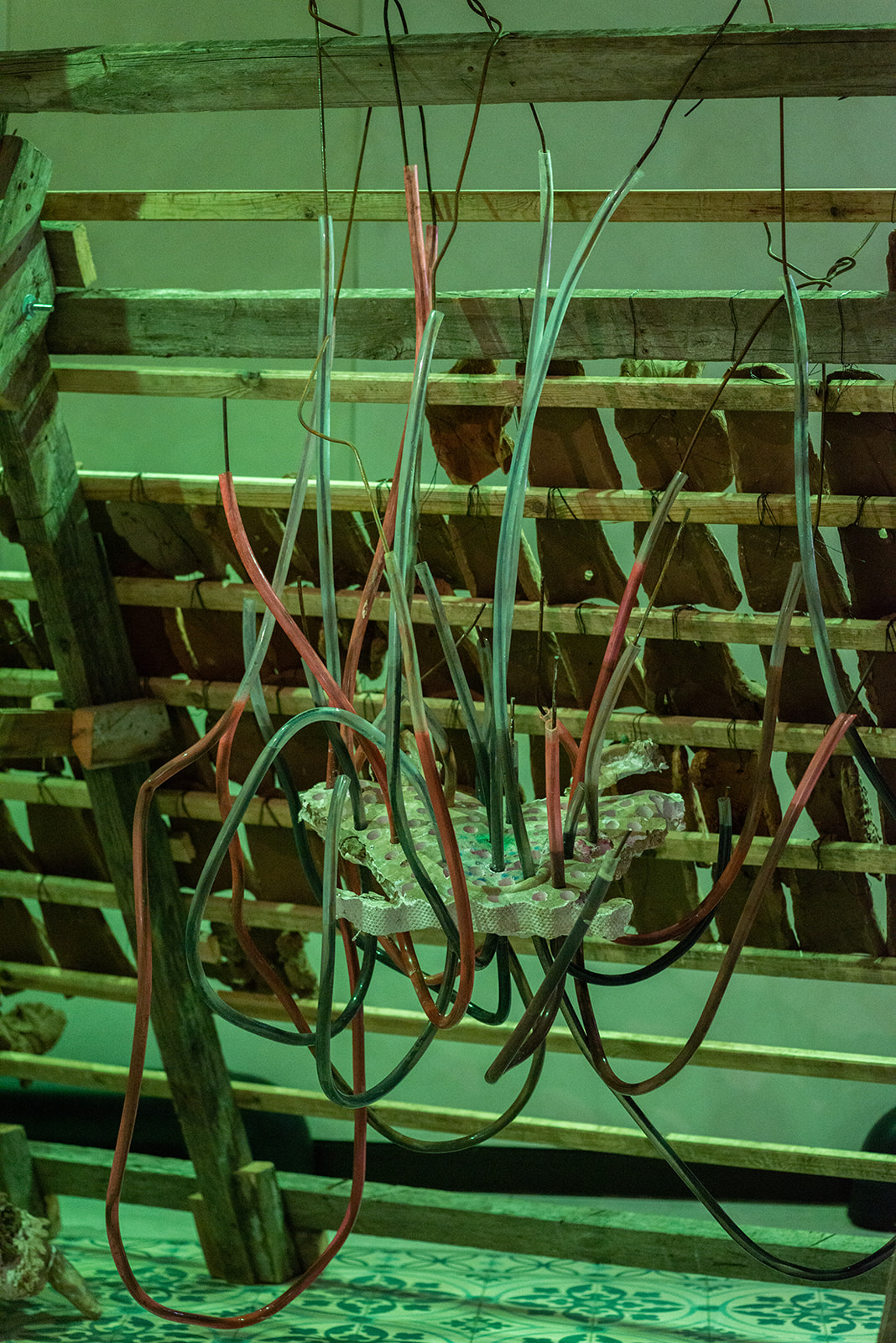

The sewer cover or manhole, in its round or latticed form, manifests as a kind of portal or gateway to another world. Whether that world is utopian or dystopian, it is, nevertheless, primal, dirty and anarchic. In an unusual collaboration with the Mei Avivim Company, we decided to invite a group of young artists to the Edmond de Rothschild Center to lift the lid and peer into the dark and abject underbelly of the sewer. Indeed, the purpose of “artistic practice is to flush out the dregs, to be a platform for what is not talked about,”[1] in the words of Galia Yahav, who curated the exhibition “Redemption from the Sewers,” in 2010. A decade later, the exhibition Spring Water asks: can wallowing in the very essence of the forbidden and the filthy bring about a purification of sorts, similar to the transformation undergone by those who bathe in the Ganges River? Can it offer a new opportunity to learn about the cycle of what enters the body and what exits it and the desalination process that turns sewage into usable wastewater? Could the sewer turn out to be not just a complex bifurcated infrastructure but also an existential, political or emotional state of being, where lives are flowing in a predetermined stream? These and other questions embodied in the various works gathered in Spring Water invite us to observe the place where “everything … converges and confronts everything else. In that livid spot there are shades, but there are no longer any secrets. Each thing bears its true form, or at least, its definitive form. The mass of filth has this in its favor, that it is not a liar. Ingenuousness has taken refuge there.”[2]

[1] Galia Yahav, “Neve habivim shel Galia Yahav,” Eli Armon Azulai, Haaretz 25.3.2010.

[2] Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, trans. Isabel F. Hapgood, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1887, vol. 5, bk 2, ch. 2, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/135/135-h/135-h.htm